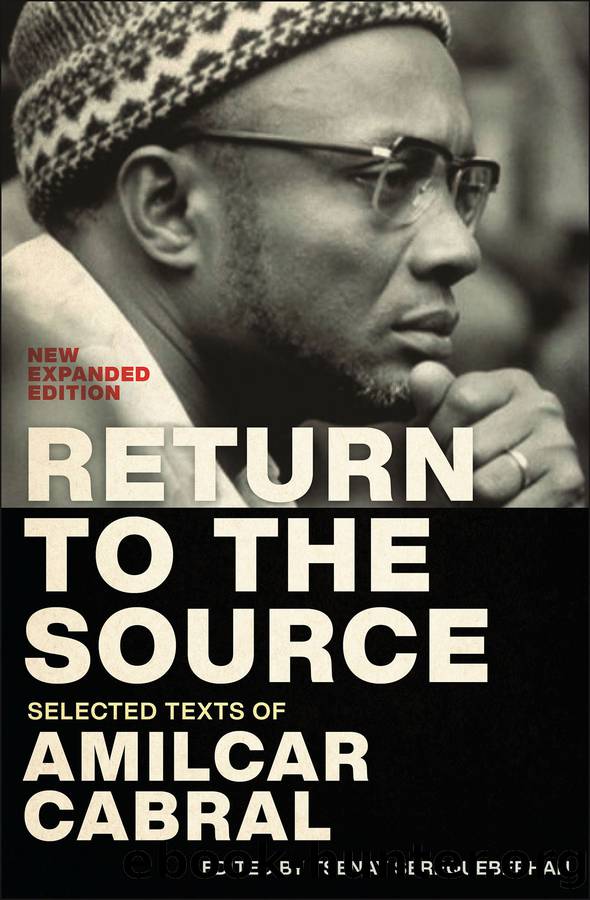

Return to the Source by Amilcar Cabral

Author:Amilcar Cabral

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: NYU Press

A third grade student in a math class at the Aerolino Lopez Cruz boarding school. At right is Sevilla-Borza, chairman of the 1973 Mission of the United Nations to the liberated Guinea. (UN PHOTO: YUTAKA NAGATA)

People of the Cubucare Sector. (UN PHOTO: YUTAKA NAGATA)

â 5 â

Brief Analysis of the Social Structure in Guinea

Condensed text of a seminar held in the Frantz Fanon Centre in Treviglio, Milan, from May 1â3, 1964

I should like to tell you something about the situation in our country, âPortugueseâ Guinea, beginning with an analysis of the social situation that has served as the basis for our struggle for national liberation. I shall make a distinction between the rural areas and the towns, or rather the urban centers, not that these are to be considered mutually opposed.

In the rural areas we have found it necessary to distinguish between two distinct groups: on the one hand, the group that we consider semi-feudal, represented by the Fulas, and, on the other hand, the group that we consider, so to speak, without any defined form of state organization, represented by the Balantes. There are a number of intermediary positions between these two extreme ethnic groups (as regards the social situation). I should like to point out straight away that, although in general, the semi-feudal groups were Muslim and the groups without any form of state organizations were animist, there was one ethnic group among the animists, the Mandjacks, that had forms of social relations that could be considered feudal at the time when the Portuguese came to Guinea.

I should now like to give you a quick idea of the social stratification among the Fulas. We consider that the chiefs, the nobles, and the religious figures form one group; after them come the artisans and the Dyulas, who are itinerant traders, and then after that come the peasants, properly speaking. I donât want to give a very thorough analysis of the economic situation of each of these groups now, but I would like to say that, although certain traditions concerning collective ownership of the land have been preserved, the chiefs and their entourages have retained considerable privileges as regards ownership of land and the utilization of other peopleâs labor; this means that the peasants who depend on the chiefs are obliged to work for these chiefs for a certain period of each year. The artisans, whether blacksmiths (which is the lowest occupation) or leather-workers or whatever, play an extremely important role in the socioeconomic life of the Fulas and represent what you might call the embryo of industry. The Dyulas, whom some people consider should be placed above the artisans, do not really have such importance among the Fulas; they are the people who have the potentialâwhich they sometimes realizeâof accumulating money. In general, the peasants have no rights, and they are the really exploited group in Fula society.

Apart from the question of ownership and property, there is another element that it is extremely interesting to compare, and that is the position of women.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19103)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12197)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8919)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6894)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6284)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5808)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5768)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5513)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5454)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5225)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5157)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5091)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4967)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4932)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4797)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4756)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4723)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4517)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4493)